“I first met my neighbor from down the street in 2004. She told me she was born in 1920 and came to Canada from Austria in 1952. While she did not reveal much more about her biography, her house spoke for her. It was stuffed to the brim with things she thought she might need one time.When years later forced to move into a retirement home, she trusted me to search for the ashes of her former husband among the layers of things she had saved. I found the ashes. Yet, her life-story she never really revealed, what made my imagination spinning and I filled the holes of narrative with creating the project “Therese”. Iris Häussler

The baroque setting of St Martin’s Monastery, the oldest Benedictine monastery in Germany, offered an intriguing backdrop for the installation of Häussler’s site-specific project “Therese.” In a small functioning guest room in the monastery’s Academy, the artist created a ghostly atmosphere. Overnight guests entered to find white linen sheets draped over windows, old wood furnishings and objects that produced shadowy forms against the white walls of the room. While the monochromatic fabrics served to conceal and unify the mismatched objects, they also held the longing and memories of a fictitious woman, Therese, who had left her homeland after World War II and never returned.

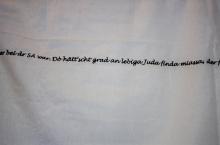

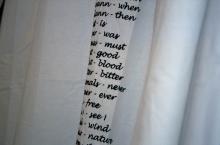

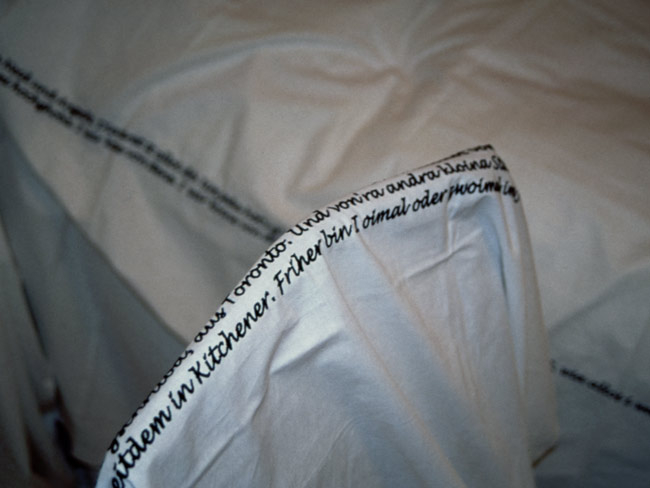

The covered furnishings collected in the room comprised Therese’s dowry, which had been left behind. Curious visitors who unveiled the furnishings could rummage through drawers and compartments to find some of Therese’s private belongings: empty picture frames, old photographs, clothespins, an embroidery frame, and a braid of dark blond hair. For those who could read her German dialect, lines of condensed black embroidered text on the surfaces of the protective linens, wove together stories of family, loss, want, necessity, uncertainty, hope and resignation that she had artfully chronicled during a 60-year period.

(Text continues after image gallery...)

Embroidered Text with Transcriptions by Prof. Norbert Feinäugle, Weingarten:

Mir hent jò älle Kraft g'het wia jonge Deifl. Sonscht nix. Koi Geld, koin Hof, koin Lada. Und nix g'lernt g'het. Was hätte mr denn macha solla? Dr Anton hòt vom Bruader vo seim Freind g'heert, dass der oifach niiberganga isch. Und dia hent an g'nomma! - war jò it iiberal so. Also der jedafalls hòt gschriiba, aus Toronto. Und von'ra andra kloina Stadt, nòch dra'. Er hòt gschriiba, dò dätat Äpfl und Woiza waxa wia dahanna und Holz kennt ma hò so viil ma wöllt. Dia lebet jetzt dò seitdem in Kitchener. Friher bin I oimal oder zwoimal im Jòhr nag'fahra. Zum Oktobrfescht. Dia hònt des zwoitgreeschte auf der Welt. Immer noh!

Really, we all were strong like young devils. But nothing more than that. No money, no farm, no store. And no education. What could we have done? Anton heard from his friend's brother that he had simply gone overseas. And they had taken him! That wasn't the case everywhere. Well, he sent a letter, from Toronto. And wrote about a little town close by. He had written about apples and wheat growing there, just like here, and you could have as much firewood as you wanted. Since then they have lived in Kitchener. I used to go there once or twice a year. At least to visit the Oktoberfest. They have the second largest in the world there, still they do.

Du denkscht, du legscht dia Gschichta von deim Leba zamma wia Wesch, wo d' auf'm Soil trocknet hòschd. Biigla duescht se, dòbei kommt dr älles klar und scharf vor d' Auga, d' Werter standet wia g'schtickt auf'm Weißa. Bis du se wiider ausenand duescht, hòt d' Zeit dra g'schafft und d' Schrift wird sogar im Dunkla blässer worda sei'. An manche Schtella isch dr des ganz recht so. Und du legscht se zamma und setzsch se aufanander, packscht se in da Koffer, nimmscht älles mit, über's Meer. Dò gibt's blos a paar, wo dia Schpròòch kennet. Und du bischt noh jung. Du wirscht vo vorna afanga.

You think you fold the stories of your life up, like laundry that's drying on the clothesline. You iron it and everything appears sharp and clear before of your eyes, the words seem to be embroidered on the white fabric. Until you unfold them again, time will have worked on them and even in the dark the writing will have faded. In some parts, it is better like this. You fold it up, stack it neatly, put it into your luggage and take it with you, across the sea. There are only a few who speak your language. And you are still young. You will make a fresh start.

Wenn zwoi Fremde sich verabredat am gleicha Ort, erkennet se sich. Se merkat's am G'sicht, dass mr ebber suacht. Wenn zwoi, wo sich kennet, sich verabredet an oim Ort, kennet se sich leicht vrpassa.

If two strangers make an appointment at a certain place they will recognize each other. They recognize the searching face. If two acquaintances do so, they might not.

I hòn zu de andre guckt volla Neid und Angscht. Dia waret it alloi dò. Um jeda hòt's g'wimmlat mit Verwandte. Ob dia g'seah hònt, wia alloi i war? ... Und oinaweag hòn i so a komischs Gfihl kriagt. So a seltsam freis Ding. Des hòt mi hochghoba. I war koine von dene. I war koine von dò drieba. I war frei.

I watched the others, feeling fear and jealousy. There was hardly someone just on his own. Relatives were bunched around everyone. Did they notice how alone I was? But I nevertheless got this strange, strong feeling. An odd thing of liberation. It lifted me up. I did not belong to them. I wasn't one of those from over there. I was free!

Dr Anton hòt mr dia Lischta in d' Hand druckt. "Dòmit kommschd durch: Meh hòn i au it braucht am Afang. Guck dir's a', guck! Dia dò driiba schwätzet oigentlich au Deitsch. Dò, guck, kaum a Unterschiid!

Anton put the list into my hand. "You'll make it with that", he said. " Even I didn't need more in the beginning. Look at it, look! They almost speak German over there. Look, more or less no difference!"

Dass oiner zrick kommt, ohne dass em dr Schwoiß rablauft. Dr Angschtschwoiß, moin I.

That someone returns without the sweat dripping from his brows. Sweat of fear, I mean.

Am Afang hòn i viil gheilt. Am Schlimmschta war's ganz am Afang. Auf am Schiff hòn i mei' Lischte rausholt. Und schnell gmerkt, dass dia ganz wenig nutzt. Dò hòn i a Mordswuat kriagt. I hòn gheilt aus Wuat, aus Vrzweiflung und schpätr aus Hoimweh.

At the beginning I cried a lot. At the very beginning it was the worst. On the ship I pulled out my list. I noticed soon that it was pretty useless. I got really upset. I got mad. I cried because I was so mad, for misery and later, for being homesickness.

D Muattr hòt d' Tiir zuag'hebt, und durch's Schlisselloch hòn-e des Muschtr von iram Schurz dunkel seha kenna. Der war bliamelat. I hòns genau heera kenna, aber älles wär besser gwesa, wenn I's au seha kenna hätt.

Mother held the door shut and through the keyhole I could make out the pattern of her apron. It was flowery. I was able to hear everything clearly, but everything would have been better if I would have been able to watch as well.

Nòch zwanzg Jòhr kennscht d' Tate glei' wiider. D' Schweschter au. Sicher. Aber nòch vierzig Jòhr? De Meischte, wo dòmòls vierzig waret, sind heit dod. Dene irna Kind schwätzet noh hi und dò im gleicha Takt. Aber dia griasset di nimma.

After 20 years you recognize your aunt of course. Your sister too. For sure. But after 40 years? Most of those who were 40 then are dead today. Their children might still talk in the same way they did. But they don't greet you anymore.

I hòn auf Brief nia zrickg'schrieba. I hòn it g'wisst, wia schreiba. I hòn's glernt g'het, sicher, aber nia g'iabt. Wia siht an Briaf aus, wo dò nagòt, wo du herkommschd? Und wia schreiba? Schwäbisch? Mei Schualdeitsch het sich au fremd ag'heert. So fremd, dass es mit mir nix meh z' do g'het hòt.

I never answered letters. I didn't know how to write. I had learned to write of course, but never practised it. What does a letter look like, that is sent to where you came from? And how to write? Swabian dialect? My school German sounded so strange. So strange that I wouldn't have had anything to do with me.

100 Mark hòn i no g'het ekschtra. Ma woiß nò nia. Oft hòn i d' Bibl aufg'schlaga und guckt, ob se noh dò sind. Dia schtecket jetzt immer noh bei Jeremia 40, aber jetzt hònt dia jò den Euro.

I kept 100 Marks aside. You never know. I often opened the Bible to look whether they were still there. They are still at Jeremiah 40, but over there they now have the Euro.

A paar sind z'rickg'floga alle paar Jòhr. Nòchdem's nimma so deier war. Und s'isch so schnell ganga.

Some took the plane back from time to time. After it had become less expensive. And it went so quickly.

Wo nò nòch a paar Jòhr gar koin Briaf meh komma isch, war's mr doch wia Datza auf d' Fingr. Mir war's jò, als hätt i mei Hoimat nia vrlassa. I bin furtganga gwea wia oina, wo am Morga aufschtòht, 's Bett macht und auf's Feld gòht. Aber d' Hoimat hòt halt mi vrlassa.

But still, when the letters stopped coming, a few years later, I felt it like the beatings I was used to as a schoolchild. You know, I didn't feel like I had left my homeland at all. I was just gone like someone who wakes up in the morning, makes her bed, and goes outside to work in the field. But my homeland had left me.